Roughly 300 years ago, after studying ancient records of eclipses, British astronomer Edmond Halley conceived of a theory that the moon was in fact physically moving away from the Earth. The moon’s recession was later confirmed in the 1970s by laser beams bouncing off mirrors placed on the moon by American and Soviet astronauts. Caused by drags in ocean tides, which slow the Earth’s spin rate, the accelerated rate compensates for the loss of angular momentum, and the moon gradually pulls away at a rate of 3.78 cm a year – about the rate at which our fingernails grow. Upon learning this, Hong Kong artist Phoebe Hui’s existing fascination with the celestial body gained newfound urgency.

Commissioned by Audemars Piguet Contemporary. Courtesy the artist and Audemars Piguet.

“For some reason, this matters to me, despite the fact it doesn’t affect us during our lifetime,” she says. Initial inspiration struck when the artist’s visited Le Brassus in Switzerland, home to Audemars Piguet’s headquarters, just after she was selected to fulfil the Fifth Audemars Piguet Art Commission, the first to be exhibited in Asia. During a nighttime stroll, an encounter with the full moon in the quiet, snowy mountains mesmerised Hui, prompting her to consider her relationship with moon and others, and nature’s interconnectedness. Seeking to recreate the impact of the experience, she returned to Hong Kong to begin her research.

This culminated in Audemars Piguet Art Commission The Moon is Leaving Us, on view from April 25 to May 23 at the Duplex Studio in Tai Kwun, Center for the Heritage and Arts, co-curated by Ying Kwok and Audrey Teichmann, Audemars Piguet Contemporary art curator. A fusion of art and technology, the installation reflects a romantic mysticism associated with the moon, while poetically translating the science behind it.

Kwok refers to the artist as a “nerdy poet”, with regard to her scientific approach, fuelled by sentimentality. A poem by eighth-century poet Li Bai, imprinted on top of a stairwell within the exhibition space, reads, “Today’s man cannot behold the moon of yore. But today’s moon did shine on men of yore.”

From literary and artistic to scientific, references to the moon’s representation in various cultural media are well documented in this exhibition. It explores how those representations have changed over time, and how we interpret and perceive them, ultimately challenging our comprehension of the universe at large.

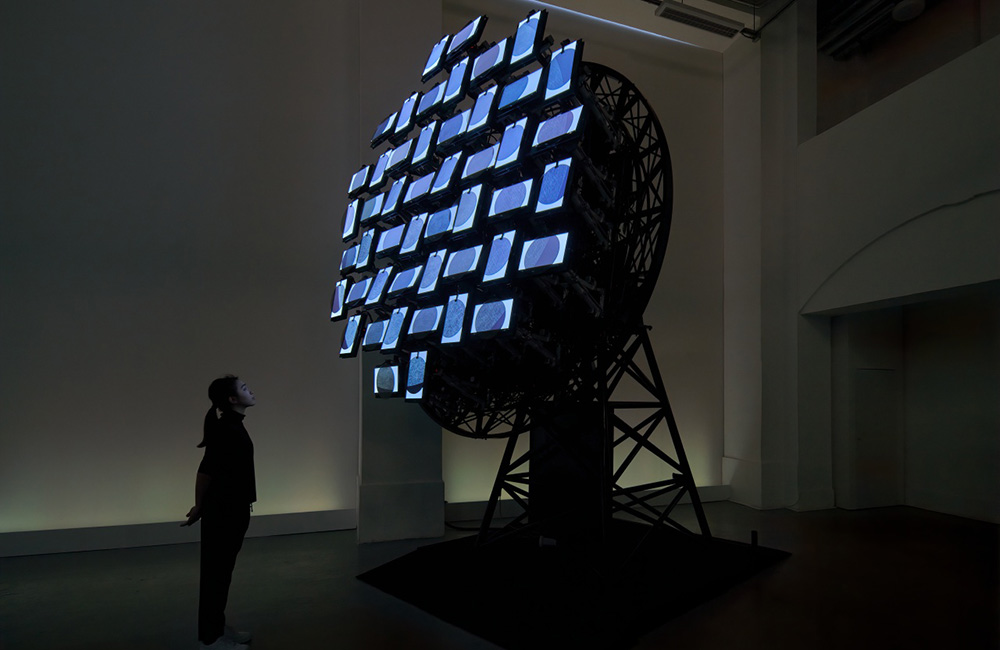

Composed of multiple elements, the commission’s most striking feature is the staggering structure Selenite (2020-21), a kinetic robot configured in a large, moon-like shape located on the lowest level of the Duplex Studio. Emitting a literal moonlit effect across the vast, high-ceilinged space, on its face Selenite projects various images of the moon on 48 mechanical arms, including some from NASA’s database. Depicting partial views of the moon, the screens together show a more complete narrative, one we rarely get to witness. In doing so, Hui highlights our limited visual perspective on nature.

She explains her decision to use multiple images with reference to conversations she and Kwok had with a former astronaut. “As the spaceship keeps orbiting, the moon can change from being a circle to an ellipse and back again. When we observe something, it’s always relative: my position in relationship to that object, and if my position changes, so does the relationship. I think this is one of the reasons I decided that Selenite should be a thread of images, not just one image.”

In considering relativity and perspective, Hui reveals an underlying intention to bring to the fore both nature and the universe’s vastness, and our own lack of awareness of what it contains. She also makes us aware that our perception of both is informed by human-made systems and instruments, stemming from particular contexts that change throughout history.

“It’s very precise and accurate, but there is human involvement,” says Kwok of the data we acquire from space. “The scientists and astronauts who derive this information have already applied certain angles to it. There is no absolute scientific objective or subjective storytelling or imagination. It’s like a gradation traveling in between that: depending on your entry point, you might be closer to one side, but once you explore and dive in, you realise there are many different angles.”

A desire to unveil the bigger picture propels Hui’s distinctive approach and her interest in kinetics. As a child, the artist would cut up Mid-Autumn Festival lanterns, initially to see how they were made, and then create something with the deconstructed pieces. While studying for her MFA, she became interested in media archaeology, a field studying new technologies through the historical lens of older media. This extends into her preoccupation with scientific philosophy: the ideas and assumptions behind scientific concepts prevail over the process themselves.

This interest is most evident in the research room created as a part of the commission, which features Selena (2021), a robotic machine built by Hui from art tools such as a canvas frame and easels. Selena produces intricate ink drawings of the moon based on updated NASA images, but with an aesthetic similar to that of 17th-century astronomer Johannes Hevelius, who meticulously documented images of the instruments he made and used to observe the moon, as well as producing a detailed atlas of the moon over four years.

A blend of old and new lunar representations are present in this series of drawings, Selenographia – WAC central longitude ink (2021), the intricacies of which can be attributed to the painstaking procedure of feeding Selena data. Thereafter, Hui proclaims, “the program needs to run through all the algorithms; the computer has to process more than 138 million parameters in order to generate images”. Selena needs to convert the algorithms into a language she understands, and then convert that into images. “If everything goes well and Selena is in a good mood, maybe it’ll take 14 hours,” says Hui of the process.

In imbuing Selena with human characteristics like this, Hui picks up on the increasing contemporary reliance on AI and robotics. Displayed in the research rooms, alongside historical depictions of the moon and documents, Selena Has a Temper is a drawing produced by the bot while it was essentially working overtime, without breaks. The aggravated sentiment is strongly evoked by its linear intensity and repetition. Drawing also speaks to the artist’s history; she used to draw and illustrate comics before she went to university. As well as with considering her practice research-based, Hui says drawing forms the basis of all her works.