By Fionnuala McHugh

In March 1968, the United States Patent Office received an application filed by one Antonio Casadei of York Road, Kowloon Tong. It was a design for an inflatable sled that could transport goods across ice and snow.

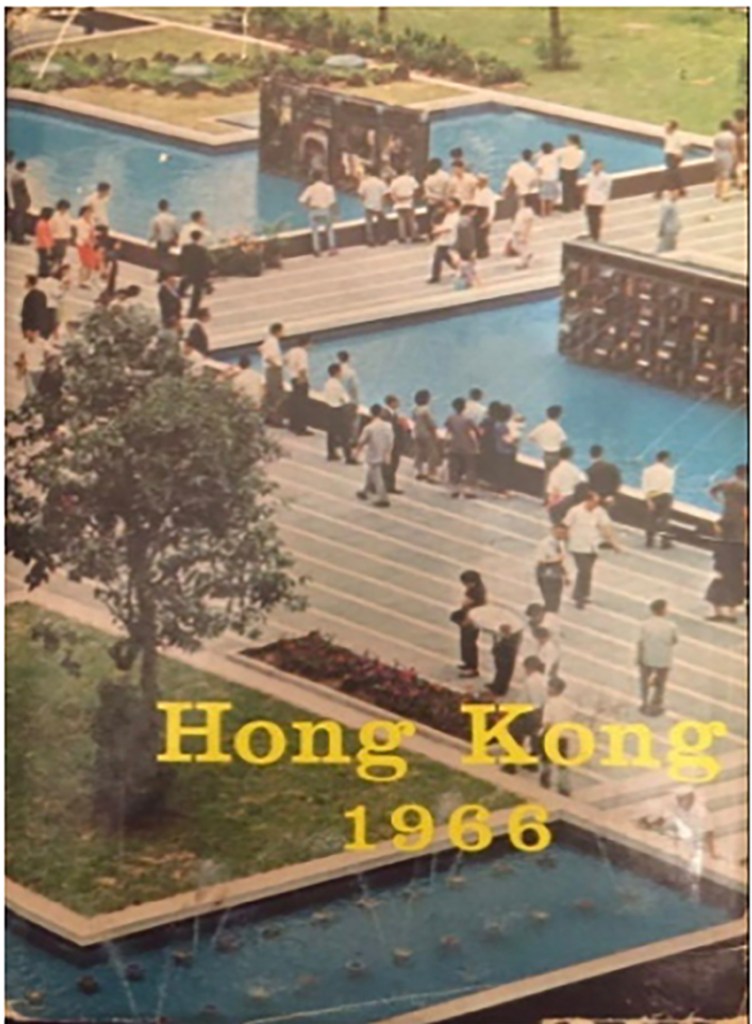

Cover 1966 Hong Kong Report.

Courtesy of Hong Kong Design Institute.

The subtropical address wasn’t the only unexpected aspect; Casadei, the hopeful inventor, was an artist in Hong Kong. His work could be seen in hotels and malls, and was already such a public attraction in Statue Square that the British colonial government had put it on the cover of its 1966 annual report.

The sled application was granted in 1970 but expired in 1987. By then, Casadei was living in Spain. After 20 years’ residence, he’d left Hong Kong in 1983, the year he turned 60. When he gave a final interview to the South China Morning Post, the headline read: ‘The artist who’s left his mark on Hongkong’. “In Hongkong, evidence of his talent lies virtually wherever one looks,” wrote the interviewer. “Almost every hotel has something or other of his.”

Design for inflatable sled.

As Casadei moved on, so did the city. These days, unless you know where to look – a restaurant in Causeway Bay, a huge housing estate in Kowloon – his mark on Hong Kong has almost vanished. He liked to carve his name in the Roman style that font designers call Caesar Brute but only a few corners still exist where you can glimpse it. On his Statue Square work, his signature is half-submerged by the fountains, although he’d probably have liked that. He had a creative affinity with water (even when it was frozen). In other places around the city, it has long run dry.

His family came from Forli, in northern Italy, where Antonio was born in 1923. His father, Maceo, was a painter and is still remembered there; one of the town’s small galleries held an exhibition of his work in November 2022. It was jauntily titled Maceo Casadei – Always at Work!.

When Antonio was 11, the family moved to Rome, where Maceo became a photographer for the Istituto Luce, or Light Institute. It had been founded by Italy’s leader Benito Mussolini to supply fascist propaganda. In May 1938, when Adolf Hitler – along with Nazi heavyweights Joachim von Ribbentrop, Rudolf Hess and Joseph Goebbels – visited Mussolini for a week, Maceo photographed the full-on fascist spectacle. (Some of his original photos from those historic seven days were stolen by a collector and only returned to the institute’s archive, which is listed in Unesco’s Memory of the World register, in July 2022.) Later, always at work, he would document World War Two in photographs, paintings and drawings.

Photo of Mussolini and Hitler in Piazza di Santa Croce a Firenze, 1938. Maceo Casedei.

Courtesy of archiviole.com.

Antonio, who turned 18, the age of military service, in 1941, took part in the war. Forty years later, in an interview, he made a single vivid reference to witnessing an orphanage being bombed. (“The soldiers just threw the dead children out of the building into the street. I took the little bodies to a nearby hill and buried them.”) So little is known about him – so few people remember him from his two decades in Hong Kong, where he kept a low social profile – that it’s difficult to measure the effects of his war. Perhaps that was its effect.

He had inherited his father’s visual aptitude. In 1943, when he was 20, he won a national photographic prize; and after the war, in the late 1940s, he worked at Cinecittà, the Italian film studios, as a cameraman. Some of his work, including a short black-and-white film of Florence’s wonders called A Portrait Signed by God, is still available online.

He painted, but ceramics were his real artistic love. By the 1950s, he was being commissioned to create large ceramic panels – in villas, in a corporate building, on a ship, in hotels – and he was also teaching art in Rome. There he met his future wife, Frances Wong, a former student of St Mary’s Canossian School in Hong Kong, who was studying art. As a result, he decided to visit Hong Kong in order to study Chinese porcelain.

In September 1962, Casadei – designated “a visiting artist” – held his first Hong Kong exhibition, at City Hall. (Frances Wong would have her own City Hall exhibition the following month.) It was opened by Luis Chan, then chairman of the Chinese Contemporary Artists’ Guild, and now recognised as Hong Kong’s most talented surrealist. Chan described him as “prolific and versatile”.

The South China Morning Post agreed. Its anonymous reviewer liked the oil paintings, the decorated glass and the “striking” sculpture in metal, but their highest praise was reserved for the “rare and beautiful” ceramic creations in which the artist seemed to excel: “He is, indeed, a discovery.”

At the time, the Mandarin Hotel was in the process of being built and its design team were next to discover him. John D’Eathe was deputy estate manager at Hongkong Land, a company that usually built offices but had, a little nervously, decided it might experiment with a hotel.

“There’s no doubt that the initial arts and design inspiration all came from Don Ashton,” remembers D’Eathe from his home in Vancouver. Ashton had been art director on David Lean’s The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) (he’d constructed the bridge), where he had learned to think in epic fashion. “When he arrived and started talking about design – and budgets – way beyond our parochial aspirations, the entire scene changed,” says D’Eathe. “We started to envisage a hotel wonderland, which then, for its day, was achieved.”

John Howorth and Frank Eckermann of Leigh & Orange, the Hong Kong architectural firm founded in 1874, worked closely with Ashton. Casadei was commissioned to create bas-reliefs for what was called the Lookout Lounge; if you grew tired of looking out, you could always admire his huge beaming sunflowers on the ceiling. In the Clipper Lounge, the tables were traced with Casadei’s golden twirls. He worked from his studio in Kowloon Tong, where he was photographed for an issue of the new hotel’s in-house magazine.

Mandarin Hotel, the Outlook Lounge, early 1960s Courtesy Leigh + Orange Archive.

He also made Chinese shadow puppets for its coffee shop. Now that his own time in the city is only the faintest outline, that seems appropriate; yet even when he was in Hong Kong, people never quite felt they knew him. “I think he would be pleased that I remember his art more clearly than his personality,” says D’Eathe. “He could speak a little English but he was not voluble like everyone else. The other guys were in some bar getting pissed. I do remember the odd coffee with him; he was a cheerful, burly young fellow. But, looking back, he was usually with one of the architects, who maybe spoke for him. So he was just that: an artistic presence hovering anxiously in the background, ensuring his art was appreciated.”

“I’d bump into him sometimes in the Mandarin,” says Brian Tilbrook, who became the Mandarin’s resident artist when it needed backdrops for events and who, now aged 91, still lives on Lamma. “He could be a bit churlish but he was more genial than Don Ashton, who was arrogant and not easy to talk to. I had great respect for Casadei’s work; he was worth his weight as an artist. Those panels he created were very effective.”

The Mandarin opened in 1963. Hongkong Land had another project, which would be unveiled to the public in 1965: a shopping mall in the newly rebuilt Prince’s Building, linked to the Mandarin by Hong Kong’s first pedestrian bridge. (The original Prince’s Building from 1904 had been designed by Leigh & Orange.) Casadei was hired to brighten the interior. He would turn up at meetings with sheaves of artistic possibilities. In honour of the building’s name, he focused on a regal theme – knights, kings, horses – mapping out designs that looked as if a medieval pack of cards were taking part in a chess game.

But he was also a ceramicist with the mind of a modern inventor. He decided to experiment with polyester resins, a type of plastic which is good for laminating surfaces such as cars and boats. After he’d embellished 140 square metres of panelling with his royals – plus their shields and galleons and rampant lions – he coated each panel with Laminac resin to make its surface gleam like ancient bronze. In the lobby hung what he claimed was “the world’s largest polyester chandelier” – seven metres long, two metres wide and five tons in weight. He’d made it from 528 pieces of cylinders, of varying length, so that it resembled a mass of stalactites and it glowed amber, red, white and yellow. “Polyester resin works in ways glass and crystal wouldn’t,” he told the South China Morning Post. “With its transparency, moldability, lustre and strength, it has great potential as a new art vehicle.”

He made that comment in December 1967 (three months before he filed his patent for the inflatable sled – vehicles were clearly on his active mind). By now, he had two children, Mara and Remo, and a stream of commissions. In 1969, his work in the new Hongkong Hotel – now the Marco Polo Hongkong Hotel – was on the cover of The Peninsula hotel’s magazine. (Hongkong and Shanghai Hotels, which owns The Peninsula, had the contract to manage it.) He made nine sculpted murals near the podium pool; he was inspired, he said later, by his underwater swimming.

His work is still around. The iconic Tai Ping Koon restaurant in Causeway Bay opened in 1970, and a Casadei work still dominates one of its walls. The Tai Ping Koon group, which currently has four restaurants in Hong Kong, traces its origins back to Chui Lo-ko, who opened the first one in Guangzhou in 1860. Andrew Chui, his great-great-grandson, says his grandfather commissioned Casadei partly because he was famous and partly because he used to eat at the Wan Chai branch. As Tai Ping Koon is considered one of the world’s first Hong Kong-western restaurants (so-called “soy-sauce cuisine”), this artistic fusion with an Italian seems apt.

Tai Ping Koon Restaurant mural with Andrew Chui’s grandfather, Causeway Bay 1970.

Courtesy Andrew Chui.

Apparently, people laughed because it was so expensive – the cost, it was said, of a Wan Chai flat – but Chui insisted. There’s a photo of Casadei at the opening; behind him, the swirling copper on fibreglass glows green and gold. In half a century, it’s darkened considerably and looms over diners but Chui says the customers still love it. If it ever had a title, he says, it’s been lost “like kitchen steam”.

By then, the Casadei family had moved to a remote house in Sai Kung, overlooking Hebe Haven, which had a duck pond, a monkey, some parrots and a fibreglass speedboat that Antonio had built himself to go fishing and diving. He’d also constructed his own shed and kiln where he could experiment with glazes and firing times. The South China Morning Post went to pay a visit one wet day in June 1970 and took a photo of him in flip-flops – not tall but broad-shouldered and square-headed – sandpapering a large fibreglass panel that represented, he said, the world under the sea. He spoke in Italian, translated by his wife.

He certainly needed the space and, perhaps, the isolation. When he was commissioned to create art for the new housing estate at Mei Foo, built from 1968 to 1978 on the old storage facilities of Mobil Oil, one of his works was an eight-metre stainless steel winged horse, Pegasus.

Pegasus at Mei Foo Sun Chuen (circa 1970-1974), Kowloon, Hong Kong.

Photo: William Furniss

It was placed in a – now waterless – fountain. Its head rears up to the sky, ignoring its surroundings, still a magnificent beast. Nearby, an aquarium of distinctive fish, each face so cleverly contrived you feel you know its character, swims in the air above a bone-dry fountain.

A vibrant ceramic panel, similar to the Casadei work at Statue Square, sits in the fountain of another courtyard. At Mei Foo, it’s easy to read the chiselled signature: there’s no water lapping at the edges.

Ceramic mural, Mei Foo Sun Chuen, 1970s. Photo: William Furniss

He died in Alicante, on Spain’s Costa Blanca, its white coast, on March 9, 2014. Some of the art from his Spanish years is for sale online; in his 80s, he was still making fish. Always at work, like his father.

In Hong Kong, he has slipped away, like rain off a hillside. On a recent afternoon at Statue Square, a group of schoolchildren sat on a fountain wall, next to his panel. A guide gave them a lecture on the square’s history: Queen Victoria, the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank, the former Supreme Court building. Asked by an onlooker if he knew who’d created the nearby artwork, the guide said no. Then he added, as a helpful afterthought: “Some artist.”

Hello Jan

That is so interesting about sleigh. Good sleuthing by Fionnuala !

Xx annabel