WYSIWYG / By Brady Ng /

Sometimes, art can leave its viewers scratching their heads. Much of it is staged to be seen from a distance in sanitised rooms, short pieces of text pasted beside it lazily flicking at pre-verbal notions. You might not engage with these objects beyond mental acrobatics or passive sensations. What you see or feel is often exactly what you get.

Though that plight persists, the emergence of participatory art in the late 1950s and early 1960s shook things up. One of the artists who sought to transform the process of viewing art into active participation in its creation, Jeffrey Shaw developed a practice that riffed off the technological developments of the day. Anyone who approaches his work is meant to handle the apparatus he designed and built – clunky monitors (now slimmed down), stationary bicycles (now more robust), dials, knobs, switches, sensors.

Shaw has been based in Hong Kong for 11 years. In 2009, he joined City University of Hong Kong as its chair professor of media art, and was dean of the institution’s School of Creative Media until 2015. Before that, he was the founding director of the ZKM Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe in Germany, and co-founded the iCinema Centre for Interactive Cinema Research at the University of New South Wales in Australia, his home country.

Courtesy the artist, Osage Art Foundation, and Centre for Applied

Computing and Interactive Media, School of Creative Media,

City University of Hong Kong.

A solo show for Shaw in Hong Kong was long overdue. WYSIWYG at Osage Gallery draws on 50 years of his artistic practice and includes objects from decades of hardware experiments as well as works that have been modified with new, smaller components.

In computer parlance, WYSIWYG, which stands for “what you see is what you get”, refers to a user interface where the layout on a screen is exactly what will be printed on paper, with the monitor displaying font effects and line breaks accurately. It was an important step in personal computing, one that made word processors more accessible to people without specialised training, fundamentally changing how humans interacted with what was new technology at the time – much as Shaw’s art draws in viewers, prompting them to physically interact with his works.

Golden Calf (1994/2018) stood at the centre of the Osage show – at the “axis mundi” of the exhibition, the artist said during a tour of it. An iPad rests on a plinth. Pick it up and the tablet’s camera detects patterns on the marble slab set on the pedestal to generate a three-dimensional rendering of the work’s titular object. Move around, and the image continually renders in real time, including reflections on the polished golden surface of its surroundings, produced by interpreting visual data piped in through four cameras set within the plinth.

Courtesy the artist and Osage Art Foundation.

Golden Calf brings together a couple of ideas. One is a direct biblical reference to the cult image that was made by the Israelites when Moses ascended Mount Sinai. The fact that it is presented in augmented reality calls to mind the frothy venture capital poured into tech startups that have a deep vocabulary of techno-marketing speak but no plans for sustainable businesses, as well as claims that the most valuable resource is no longer oil but data – virtual slivers of information that describe our movements, habits and personalities.

Another concept embedded in the work is our relationship with technology. To fully experience the work, we need to handle the tablet, aim it properly, walk in a circle and view it on a screen. The original iteration of Golden Calf involved a clunky 13-inch monitor with a sign that read “pick me up” attached to it, because people weren’t used to handling visual output devices in such a way a quarter-century ago. This arrangement augured the prevalence of “black mirrors” in our lives, as well as our dependence on such devices to remain connected to other people. Though originally intended as a playful system, handling the iPad in Golden Calf can be a disorienting experience. Accessing the work requires situational awareness in physical space combined with attentive mental focus on a virtual environment. Our gaze is never meant to leave the “statue” of a false god.

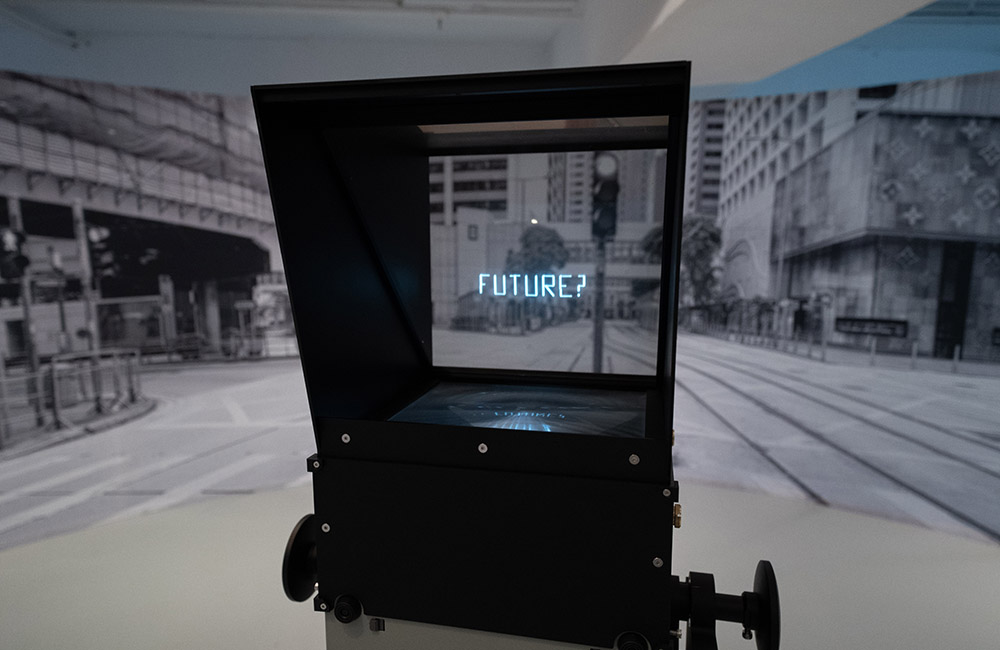

Another of Shaw’s works, Virtual Sculptures (1981/2019) also requires viewers/participants to experience the installation on circular footpaths. As one of the world’s first augmented reality art works, it was an exercise in fusing tech with art, featuring a design that prompts the viewer to take control and operate it. A CRT monitor is mounted on a tripod, screen side up. Using a Fresnel lens and a semi-transparent mirror, graphics generated by an Apple II computer – including wireframe images of a cube, and a plane from the first Flight Simulator video game – are projected into our physical space, viewable only through a black box that is on top of the whole setup.

Courtesy the artist, Osage Art Foundation, and Centre for Applied Computing and

Interactive Media, School of Creative Media, City University of Hong Kong.

At Osage, the tripod was placed within a blown-up Cycloramic photograph produced by Hong Kong photographer John Choy depicting the city’s central business district without people shortly after 6am. The names of businesses including luxury-brand shops and bank branches have been removed, with the spaces left blank, though reflections of their logos and signs remain on glossy surfaces. Other traces tell us what the city is going through: a makeshift roadblock remains on a road that is normally packed with traffic, and Chinese graffiti reads “Hong Kong add oil”, a popular slogan that is posted on social media, painted all over the city and shouted out of windows at night.

Like Golden Calf, viewers are compelled by the setup of Virtual Sculptures to grip the work and move with it. Take it to the right bearing, tilt it to the proper angle and look into the box, and you’ll see the computer-generated fragment “FUTURE?” floating before the vacant street. That graphic was present in the original work too, but its latest iteration taps into new uncertainties and anxieties that have emerged in Hong Kong.

The interplay between work and physical input continues in Eavesdrop (2004/19), which the artist calls a “film that is not a film”. Step inside and you’ll find a mounted projector ready for you to rotate and aim at a cylindrical projector screen. Depending on where the projector points, a different narrative unfolds and the viewer, peering into a club, eavesdrops on conversations between pairs of characters, including a mafioso and his puppet lover, an older married couple who pretend that they are strangers, and a journalist and his interview subject – a revolutionary or terrorist who blows himself up after nine minutes, killing everyone in the club who is still alive at that point (the older couple kill themselves beforehand). The video loops back to the beginning, and we realise that two men seated next to each other are aware that, for all who are in the premises, time folds onto itself. They need to relive their deaths over and over again, dying every nine minutes.

Courtesy the artist, Osage Art Foundation, and Centre for Applied Computing and

Interactive Media, School of Creative Media, City University of Hong Kong.

Though time carries the narrative forward, the viewer determines what information is revealed. It’s like a video game controlled from a first-person point of view; there is a narrow, limited field of vision and sound, and we are forced to abandon all sense of periphery. To piece together the entire scene, we need to be nimble and direct the projector’s lens to different portions of the screen.

Other works in WYSIWYG demanded viewers’ participation too, like Fall Again, Fall Better (2012), where we step onto a mat to make digitally rendered puppets collapse; or Legible City (1989–91), where we pedal on a stationary bicycle to navigate Manhattan, Amsterdam or Karlsruhe, reading text along the streets that forms stories about each city. And in Recombinatory Poetry Wheel (2018), we twist a knob to splice together snippets from poems by Singapore’s Edwin Thumboo, recited by the man himself. These works only function properly if we contribute.

Shaw uses technology to drive home the point that art is your business too: that it doesn’t need to be something haughty, housed in sterile, bleak, imposing environments. Perhaps this is best encapsulated by Waterwalk (1969/2019), a PVC tetrahedron filled with air that people can step within and traverse the surfaces of lakes, rivers and oceans. It was a project by the Eventstructure Research Group, of which Shaw was a member. At Osage, the artist showed footage of the original demonstration in Amsterdam in 1969 on a boxy CRT monitor, as well as of a restaging during the 2019 Venice Biennale on a much thinner LCD screen. Everyone who tried it emerged from the bubble with a cheek-to-cheek grin. How could they not? Art had just literally given them the chance to walk on water.

藝術,有時候是會令人摸不著頭腦。大多數的藝術品都只可以在經消毒的房間內遙距地觀看,旁邊會黏貼著一小段文字,慵懶地輕描藝術家的創作概念。你未必可以在心理或被動感官外體驗到這些作品,因為你看到或感覺到的通常就是你的所得。

雖然這問題至今仍然存在,但在1950年代末和1960年代初首現的參與式藝術已足以震驚世界。其中一位嘗試將觀看藝術的過程轉變為積極參與的藝術家就是邵志飛,他提出的實踐方法顛覆了當時的科技發展,所有接近他作品的人都要參與他設計和製造的裝置——笨重的屏幕(現在已變輕型)、單車(現在已變穩固)、鐘面、把手、開關和感應器。

邵志飛在香港居住了11年。2009年,他加入香港城市大學擔任媒體藝術講座教授,並擔任該學院院長至2015年。加入城大前,他創辦了德國卡爾斯魯厄ZKM媒體藝術中心,並在他的祖國澳洲聯合創辦了悉尼新南威爾斯大學的互動電影研究中心iCinema中心。

邵志飛的香港個展可謂姍姍來遲。奧沙畫廊的「WYSIWYG」回顧了他50年的藝術實踐經驗,包括數十年來作硬件實驗的物件和已被較小的新組件取代的作品。

在電腦術語中,「WYSIWYG」即「所見即所得」,是指一種屏幕佈局會準確顯示字體效果和換行,與列印效果完全相同的用戶界面。這種界面是個人電腦的重要功能,令即使沒有經過專門培訓的人都可輕易使用文字處理器,徹底改變了人類與當時的新科技之間的交流,如同邵志飛的藝術吸引觀眾與作品互動一樣。

展覽的中心是《Golden Calf》(1994/2018年),藝術家在導賞中更形容作品為「宇宙軸」。基座上有一部iPad,觀眾拿起後,iPad的鏡頭會檢測基座雲石板上的圖案,產生作品主角的立體透視圖。移動iPad時,畫面會不斷產生實時圖像,包括四周物件在拋光的金色表面上的反射,透過分析底座四個鏡頭輸入的視像數據而成。

《Golden Calf》反映了藝術家一系列的想法。一是直接引述聖經中摩西登上西奈山時以色列人所拜的偶像。擴增實境令人想起泡沫風險投資於科技初創企業的湧入:公司談起科技營銷時詞彙豐富,但卻沒有可持續的發展計劃,認為最有價值的資源不再是石油,而是描寫我們的行為、習慣和個性的虛擬數據。

作品的另一概念是人類與科技的關係。要全面體驗作品,觀眾需要拿起平板電腦,正確對準目標並圍圈走,才可以在屏幕上看到主角。《Golden Calf》起初是一個笨重的13吋屏幕,25年前人們不知道如何使用視覺輸出設備,因此屏幕貼上了「拿起我」字樣。作品的體驗預示了科技產品的盛行,以及人類溝通時對這些設備的依賴。儘管在《Golden Calf》中操作iPad是個有趣的體驗,但某程度上卻會令人迷失方向。操作作品需要現實空間的態勢感知以及對虛擬環境的專注,目光不可離開假神的「雕像」。

邵志飛的另一件作品《Virtual Sculptures》(1981/2019年)同樣需要觀眾沿裝置圍圈走來體驗。作為世界上其中一件最早期的擴增實境作品,它把科技融合藝術,讓觀眾進行控制和操作。螢光幕顯示器安裝在三腳架上,屏幕朝上。透過菲涅耳透鏡和半透明鏡,把Apple II電腦生成的圖形(包括立方體的線框圖像和第一個模擬飛行電動遊戲中的飛機)投影到觀眾的現實空間中,只能透過膈置頂部的黑盒觀看。

至於在奧沙畫廊的展覽中,三腳架就被放置在一幅由香港攝影師蔡旭威拍攝的放大版環繞全景相片中。相片的背景是早上6時無人的中環商業區,名店和銀行的公司名稱被除去並留白,光滑的表面上留下標誌的反射。相片上的其他痕跡揭示出這座城市正經歷的大大小小:平日人滿為患的道路上的臨時路障、「香港加油」中文塗鴉——一句在社交媒體上流傳、塗滿了整個城市和每晚都會從窗戶聽到的流行口號。

與《Golden Calf》一樣,《Virtual Sculptures》亦需要觀眾拿起作品並隨其移動。把作品放到正確的方位,將其傾斜到適當的角度,然後看一下黑盒,你會看到電腦生成的「未來?」碎片在空蕩蕩的街道前漂浮。初期的版本亦載有相同圖案,但最新版本更觸碰了香港社會近期的未知和憂慮。

作品和現實參與之間的互動在《Eavesdrop》(2004/19年)中仍然可見,藝術家稱之為「不是電影的電影」。走進作品中,你會發現一部安裝好的投影機,讓你旋轉並對準圓柱形的投影機屏幕。裝置會根據投影機所指向的地方,播放並讓觀眾偷聽眼前所看到的俱樂部中不同人物的對話,包括黑手黨成員和他的木偶情人、一對扮成陌生人的老夫婦以及一名記者還有他的受訪對象。這名受訪對象是個革命/恐怖分子,9分鐘後,他炸死了自己和俱樂部的所有人(但老夫婦在那之前自殺了)。影片重播到最開始時,觀眾會發現其中兩個同坐的男人早知道即將會發生的爆炸。對於在場的所有人來說,時間一點一點地消逝。他們每9分鐘死亡一次,然後又再次復活。

儘管故事的推進是由時間控制,但觀眾仍可選擇所顯示的信息。就像在第一人稱視角電動遊戲中,視覺和聲音狹窄有限,迫使玩家放棄所有邊緣感一樣。要拼合整個場景,觀眾需要保持敏捷,並將投影機的鏡頭對準屏幕的不同部分。

「WYSIWYG」的其他作品亦講求觀眾親身參與,例如在《 Fall Again, Fall Better》(2012年)中,觀眾要踩在墊子上令電子木偶倒下。在《Legible City》(1989-91年)中,觀眾要踩單車探索曼克頓、阿姆斯特丹或卡爾斯魯厄,沿著街道閱讀每個城市的故事。在《Recombinatory Poetry Wheel》(2018年)中,新加坡詩人唐愛文會朗誦其詩歌,觀眾需要扭轉把手,將詩歌摘錄拼接在一起。只有觀眾的參與,這些作品才能正常運作。

邵志飛利用科技令人明白藝術與人類息息相關,無須將藝術標籤為高傲、乏味、單調或遙不可及之物,也許以《Waterwalk》(1969/2019年)作解釋就最好不過。作品是個充滿空氣的PVC四面體,觀眾可以進入其中,感覺穿越湖泊、河流和海洋的表面。作品是Eventstructure Research Group的項目,而邵志飛就是其中一員。在奧沙畫廊的展覽中,藝術家用一台方形的螢光幕顯示器顯示了作品於1969年在阿姆斯特丹展出時的片段;並透過纖薄的LCD屏幕展示出2019年威尼斯雙年展的展出片段。每個體驗過的觀眾步出時都面露笑容,無他,因為藝術確實地給予他們在水上行走的機會。